Abstract

Introduction. Falls among older adults (age ≥65) are a common and costly health issue. Knowing where falls occur and whether this location differs by sex and age can inform prevention strategies. Objective. To determine where injurious falls that result in emergency department (ED) visits commonly occur among older adults in the United States, and whether these locations differ by sex and age. Methods. Using 2015 National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-All Injury Program data we reviewed narratives for ED patients aged ≥65 who had an unintentional fall as the primary cause of injury. Results. More fall-related ED visits (71.6%) resulted from falls that occurred indoors. A higher percentage of men’s falls occurred outside (38.3%) compared to women’s (28.4%). More fall-related ED visits were due to falls at home (79.2%) compared to falls not at home (20.8%). The most common locations for a fall at home were the bedroom, bathroom, and stairs. Conclusion. The majority of falls resulting in ED visits among older adults occurred indoors and varied by sex and age. Knowing common locations of injurious falls can help older adults and caregivers prioritize home modifications. Understanding sex and age differences related to fall location can be used to develop targeted prevention messages.

Keywords: accidental falls, aged, circumstance, injury, elderly

‘Older adult falls are preventable. There are evidence-based strategies that health care providers can implement to reduce fall risk in their older patients.’

Falls are a common cause of injuries in older adults, those aged 65 and older. 1 Each year 1 in 4 older adults falls. 2 While not all falls result in injury, each year approximately 3 million older adults are seen in an emergency department (ED) for fall-related injuries, more than 950 000 are hospitalized as a result of these injuries, and over 32 000 die because of an unintentional fall. 1 From 2009 to 2018, the age-adjusted fall death rate for older adults increased by about 30%.3,4

Older adult falls are preventable. There are evidence-based strategies that health care providers can implement to reduce fall risk in their older patients. 5 Information about location of falls in older adults may help inform which of these strategies could be prioritized for older adults at increased risk of falling. For example, for indoor falls in the home, certain home modifications (such as installing grab bars in bathrooms, removing throw rugs in living spaces), when suggested by an occupational therapist, have been shown to effectively reduce the rate of falls in older adults. 5

Previous studies have shown that older adults are more likely to fall or be injured from a fall indoors than outdoors.6-10 However, only one of these studies used nationally representative data, 10 which were collected between 2001 and 2003. Older adults are also more likely to be injured from a fall,10,11 or die from a fall in the home compared to falls that occur in public places. 12 The frequency of both indoor falls and fall-related ED visits because of an indoor fall increase with age.8,13 However, research on differences between the location of falls and fall injuries by sex are inconclusive.6-8,11,14 Few studies have investigated specific fall locations (such as bedroom, bathroom, etc) and those that did were either not specific to older adults11,13,15 or were not conducted in the United States. 16

The objective of this study was to determine common locations of falls that result in ED visits in a nationally representative population of older adults and to determine if these locations vary by demographic characteristics including age group and sex.

Methods

Narratives from the 2015 National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–All Injury Program (NEISS-AIP) were reviewed to determine the locations of nonfatal fall injuries among adults age 65 and older. NEISS-AIP, a nationally representative data system operated by the US Consumer Product Safety Commission, captures data on ED visits that result in an injury. NEISS-AIP includes data from a sample of 66 of 100 NEISS-participating hospitals in US states and territories weighted to represent the US population using the inverse probability of hospital selection in each stratum and adjusted for nonresponse. 17 For each ED visit, the precipitating cause of injury, principal diagnosis, primary body part injured, and location of the fall were abstracted. Only ED visits in which the precipitating cause, as noted in the ED record, was an unintentional fall were included in the analysis. The location of injury indicator, provided in the NEISS-AIP dataset, included the following locations: home, public, street, industry, school, farm, apartment, sports, or mobile home. Additional information regarding whether these falls occurred indoors or outdoors, or at a specific site (such as bathrooms, yards, kitchens, etc) could only be determined from the narratives.

There were 38 654 ED records of unintentional nonfatal fall injuries among older adults. NEISS coordinators abstract injury-related ED records at participating EDs each day providing information for NEISS variables and a narrative of up to 2 lines of text explaining the circumstances of the injury. 18 For our analysis narratives were divided evenly and coded by 1 of 4 researchers. A codebook was developed (Appendix A, available online) by reading 100 narratives and then updated for every 2000 narratives coded. Ten percent of all narratives were reviewed by a second researcher, and coding discrepancies were discussed among 4 researchers until consensus was reached. Previous narratives were recoded based on changes made to the codebook.

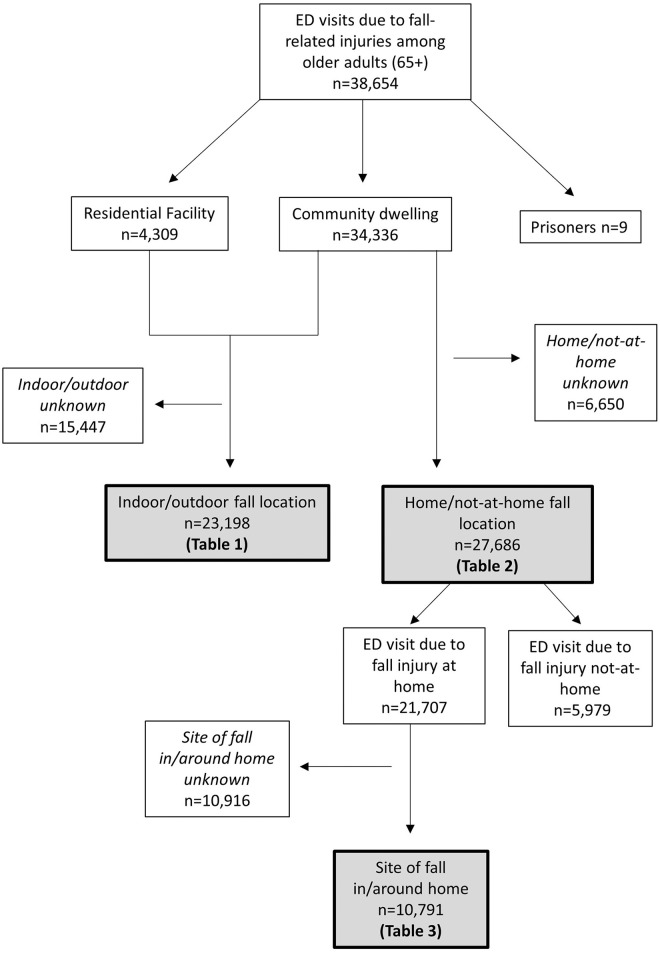

Using the narrative text we coded location of a fall by 3 separate categories: (1) indoor versus outdoor, (2) home versus not-at-home, and (3) sites in and around the home (specific rooms, stairs, driveway, yard, etc; Appendix A). Additionally, we coded residential status of older adults into community-dwelling, residential facility (eg, nursing home, assisted living, or long-term care) or prison (Appendix A). Those living in prison were excluded due to small sample size (n = 9) leaving 38 645 narratives. Out of the remaining narratives, we were able to determine indoor versus outdoor location for 23 198 narratives (Figure 1). Only the narratives for community-dwelling older adults (n = 34 336) were used to identify if the fall occurred at home or not-at-home. The narratives of 15 328 community-dwelling older adults provided sufficient information on whether the fall occurred at home or not-at-home. To address the low sample size for this variable, we also used the location indicator available in the NEISS-AIP dataset. We coded as home when the NEISS-AIP variable indicated home, apartment, farm, or mobile home. Older adults who fell at their own residence or at the residence of another person were both included in the category of “Home.” Not-at-home indicated public, street, industry, school, or sports location. This increased the sample size to 27 686. Out of the 21 707 falls that occurred at home, 10 791 narratives could be used to determine the specific sites of these falls around the home (bathroom, bedroom, yard, patio, etc; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart outlining how the samples used for analyses were derived, 2015 National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–All Injury Program.

Analysis

Weighted frequencies, percentages, and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals for fall-related injuries that resulted in ED visits (hereafter called “fall-related ED visits”) were calculated for fall location (indoor vs outdoor, home vs not-at-home, and sites in or around the home), sex, age group, and residential status. Analysis of indoor versus outdoor, home versus not-at-home, and at-home location of falls were limited to narratives where location could be described. To take into account the variability that can occur when subsets of data are analyzed, domain analysis was used 19 with the NEISS-AIP survey weights to produce national estimates of fall-related injuries that resulted in ED visits. Where estimates were based on less than 30 observations, percentages and confidence intervals were not reported. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 survey procedures to account for sample weights and the complex survey design.

Results

The narratives from 38 654 unintentional fall-related ED visits in older adults were reviewed, representing over 3 million ED visits in 2015. Older women had more fall-related ED visits (estimated 1 997 090 ED visits or 7.5 ED visits per 100 older women) than older men (estimated 1 040 460 ED visits or 4.9 ED visits per 100 older men). Indoor/outdoor location of falls could be determined for 60.8% of estimated ED visits. The majority of these visits were from falls that occurred indoors (71.6%; Table 1). Indoor falls made up the majority of fall-related ED visits for both community-dwelling older adults (68.2%) and older adults living in residential facilities (98.2%; Table 1). An estimated 28.4% of falls resulting in ED visits could be classified as having occurred outdoors. Indoor versus outdoor location of falls for community-dwelling older adults differed by sex and age group, where location could be determined. For women, 71.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 70.7, 72.6) of ED visits for fall injuries occurred indoors and 28.4% (95% CI: 27.4, 29.3) occurred outdoors. For men, 61.7% (95% CI: 60.3, 63.1) of fall injuries occurred indoors and 38.3% (95% CI: 36.9, 39.7) occurred outdoors (Table 1). For community-dwelling adults aged 85 and older, 79.4% (95% CI: 78.1, 80.7) of ED visits for fall injuries occurred indoors. In the 65- to 74-year age group, 58.8% (95% CI: 57.4, 60.2) had an ED visit due to a fall that occurred indoors (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Fall Location and Demographic Characteristics of Adults (Age ≥65) Who Sought Emergency Department Care for a Fall-Related Injury by Residential Status, 2015 National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–All Injury Program (Sample n = 23 198 a ).

| Residential status | Indoor | Outdoor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample n | Weighted b % | 95% CI | Sample n | Weighted b % | 95% CI | |

| Community dwelling | 14 131 | 68.2 | (67.4, 69.0) | 6485 | 31.8 | (31.0, 32.6) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 4392 | 61.7 | (60.3, 63.1) | 2794 | 38.3 | (36.9, 39.7) |

| Female | 9739 | 71.6 | (70.7, 72.6) | 3691 | 28.4 | (27.4, 29.3) |

| Age group | ||||||

| 65-74 | 4334 | 58.8 | (57.4, 60.2) | 3001 | 41.2 | (39.8, 42.6) |

| 75-84 | 4880 | 68.0 | (66.7, 69.4) | 2253 | 32.0 | (30.6, 33.3) |

| 85+ | 4917 | 79.4 | (78.1, 80.7) | 1231 | 20.6 | (19.3, 21.9) |

| Residential facility | 2531 | 98.2 | (97.6, 98.8) | 51 | 1.8 | (1.2, 2.4) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 755 | 96.7 | (95.1, 98.4) | — c | — c | — c |

| Female | 1776 | 98.8 | (98.2, 99.4) | — c | — c | — c |

| Age group | ||||||

| 65-74 | 310 | 99.2 | (98.4,100.0) | — c | — c | — c |

| 75-84 | 662 | 97.2 | (95.6, 98.8) | — c | — c | — c |

| 85+ | 1559 | 98.4 | (97.7, 99.2) | — c | — c | — c |

| Total | 16 662 | 71.6 | (70.9, 72.3) | 6536 | 28.4 | (27.7, 29.1) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department.

Of the 38 654 unintentional fall-related ED visits, only 23 198 had information on whether the fall occurred indoors or outdoors.

Estimates are weighted to the 2015 US population.

Cell counts <30 are unstable and therefore not reported.

The majority of fall-related ED visits among community-dwelling older adults occurred at home (79.2%, 95% CI: 78.6, 79.8; Table 2). When home versus not-at-home location could be determined, falls that occurred at home versus not-at-home did not vary by sex but did vary by age group. For adults 65 to 74 years old, 25.4% (95% CI: 24.3, 26.5) of falls did not occur at home but only 16.2% (95% CI: 15.2, 17.2) of adults 85 and older who went to the ED because of a fall, did not fall at home (Table 2). Among those aged 65 to 74 years, 74.6% (95% CI: 73.5, 75.7) of falls occurred at home, followed by 79.9% (95%CI: 78.9, 80.9) among those aged 75 to 84, and 83.8% (95% CI: 82.8, 84.8) for those 85 and older.

Table 2.

Percent of Community-Dwelling Older Adult (Age ≥65) Fall-Related Emergency Department Visits by Home and Not-At-Home Location, 2015 National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–All Injury Program (Sample n = 27 686 a ).

| Home | Not-at-home | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample N | Weighted b % | 95% CI | Sample N | Weighted b % | 95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 7396 | 78.6 | (77.6, 79.6) | 2242 | 21.4 | (20.4, 22.4) |

| Female | 14 311 | 79.6 | (78.8, 80.3) | 3737 | 20.4 | (19.7, 21.2) |

| Age Group | ||||||

| 65-74 | 7191 | 74.6 | (73.5, 75.7) | 2645 | 25.4 | (24.3, 26.5) |

| 75-84 | 7550 | 79.9 | (78.9, 80.9) | 1966 | 20.1 | (19.1, 21.1) |

| 85+ | 6966 | 83.8 | (82.8, 84.8) | 1368 | 16.2 | (15.2, 17.2) |

| Total | 21 707 | 79.2 | (78.6, 79.8) | 5979 | 20.8 | (20.2, 21.4) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department.

Of the 34 336 unintentional fall-related ED visits among community-dwelling older adults only 27 686 had information on whether the fall occurred at home or not-at-home.

Estimates are weighted to the 2015 US population.

The bedroom (25.0%, 95% CI: 24.0, 26.0), followed by stairs (22.9%, 95% CI: 21.9, 23.9) and bathrooms (22.7%, 95% CI: 21.7, 23.7) were the most common places for falls to have occurred in or around the home (Table 3). Among falls that occurred at home, 5.6% (95% CI: 4.7, 6.6) occurred in the kitchen for men and 8.1% for women (95% CI; 7.3, 8.9). For men, 7.8% of falls occurred in the driveway/garage (95% CI: 6.7, 8.9). The driveway/garage only accounted for 5.0% (95% CI: 4.4, 5.7) of women’s falls at home (Table 3). For adults 85 and older, a high percentage of falls occurred in the bedroom (31.6%, 95% CI: 29.7, 33.6) with only 19.8% (95% CI: 18.2, 21.4) in those aged 65 to 74 years and 24.2% (95% CI: 22.5, 25.9) in those aged 75 to 84 years. For adults in the 65 to 74 age group, a higher percentage of ED visits were due to a fall on the stairs (30.0%, 95% CI: 28.1, 31.8) than any other place at home (Table 3).

Table 3.

The Specific At-Home Site for Fall-Related ED Visits for Community-Dwelling Adults (Age ≥65), 2015 National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–All Injury Program (Sample n = 10 791 a ). b

| Location at home | Total | Sex | Age group | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | 65-74 | 75-84 | 85+ | ||||||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Bedroom | 25.0 | (24.0, 26.0) | 23.6 | (21.9, 25.3) | 25.8 | (24.5, 27.1) | 19.8 | (18.2, 21.4) | 24.2 | (22.5, 25.9) | 31.6 | (29.7, 33.6) |

| Stairs | 22.9 | (21.9, 23.9) | 23.2 | (21.5, 24.8) | 22.7 | (21.5, 24.0) | 30.0 | (28.1, 31.8) | 22.2 | (20.6, 23.9) | 16.0 | (14.5, 17.6) |

| Bathroom | 22.7 | (21.7, 23.7) | 22.0 | (20.3, 23.7) | 23.1 | (21.9, 24.3) | 19.8 | (18.2, 21.4) | 22.5 | (20.9, 24.2) | 26.1 | (24.2, 28.0) |

| Kitchen/dining room | 7.2 | (6.6, 7.8) | 5.6 | (4.7, 6.6) | 8.1 | (7.3, 8.9) | 6.2 | (5.2, 7.2) | 7.8 | (6.7, 8.9) | 7.6 | (6.5, 8.7) |

| Driveway/garage | 6.0 | (5.4, 6.6) | 7.8 | (6.7, 8.9) | 5.0 | (4.4, 5.7) | 6.0 | (5.0, 7.0) | 7.1 | (6.1, 8.1) | 4.8 | (3.8, 5.7) |

| Yard | 5.5 | (4.9, 6.0) | 6.5 | (5.5, 7.5) | 4.9 | (4.3, 5.5) | 6.2 | (5.2, 7.2) | 5.8 | (4.9, 6.8) | 4.3 | (3.4, 5.1) |

| Living room | 4.8 | (4.2, 5.3) | 3.9 | (3.2, 4.7) | 5.2 | (4.5, 5.9) | 4.1 | (3.3, 4.9) | 4.7 | (3.8, 5.5) | 5.5 | (4.5, 6.5) |

| Porch | 3.0 | (2.6, 3.4) | 3.1 | (2.4, 3.7) | 2.9 | (2.4, 3.4) | 3.5 | (2.8, 4.3) | 3.1 | (2.4, 3.7) | 2.3 | (1.6, 2.9) |

| Other c | 3.0 | (2.6, 3.4) | 4.2 | (3.5, 5.0) | 2.3 | (1.8, 2.7) | 4.4 | (3.6, 5.3) | 2.6 | (1.9, 3.2) | 1.8 | (1.3, 2.4) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department.

Of the 21 707 unintentional fall-related ED visits that occurred at home, only 10 791 had information about the room or area around the home in which the fall occurred.

All percentages were calculated from weighted estimates, estimates are weighted to the 2015 US population.

Other includes falls in the basement, hallway, pool, ramp, farm/ranch, and roof.

Discussion

This study found that the majority of fall-related ED visits among older adults were due to falls that occurred indoors. This was true for both sexes and all age groups. Where location could be determined, indoor falls accounted for 71.6% of women’s fall-related ED visits and 61.7% of men’s. Our findings are similar to a study in the Netherlands, which found that older adults’ fall-related ED visits were more likely due to falls indoors than outdoors and a higher percentage of older men’s fall-related ED visits were from outdoor falls. 6 In the MOBILIZE Boston study, Duckham et al explored self-reported falls and fall injuries in a cohort of 765 older adults and found women had a higher rate of fall injuries overall and a higher rate of indoor fall injuries per person year than men. 7 However, the rate of outdoor fall injuries per person year did not differ between the sexes. 7 A possible explanation for the gender differences is differences in exposure to specific environments. Older men reported spending more time engaged in recreational activities than older women and older women reported spending more time doing light housework compared to older men, which could explain some of the variation in fall location observed between men and women. 7

Two studies used data from the National Health Interview Survey to assess location of medically treated fall injuries.10,11 Both studies found that fall injuries for which older adults sought medical treatment were more likely to occur in their homes compared to public locations. This is similar to our findings which show that the home was the most commonly reported location of fall-related ED visits among community-dwelling older adults, particularly among those 85 and older. This could be due, in part, to older adults spending more time at home than at public places. However, this could not be determined from the study data.

Among fall-related ED visits that occurred at home, most occurred in the bedroom, stairs, or bathroom. This was most evident among adults 85 and older. An Australian study found, among older adults discharged from the hospital in the past 6 months, the most commonly listed location of falls and fall injuries was the bedroom. 16 This was potentially related to older adults using fewer fall prevention strategies in their bedrooms, such as limited use of assistive devices around their bedrooms. 16 It is also possible differences in locations around the home are related to the time spent in specific rooms. For example, older adults may spend more time in their bedrooms than other locations. Specifically, the Hill et al study focused on patients recently discharged from the hospital. Older adults may experience functional decline as a result of low mobility while hospitalized, 20 which could result in them spending more time in their bedrooms postdischarge. Our study is not limited to those recently discharged from the hospital, which may explain the high percentages of fall injuries in other places such as bathrooms or on stairs.

There are effective, evidence-based fall prevention strategies that could be improved upon by using these data on fall location. For example, home modifications conducted by a health care professional, such as an occupational therapist, have been shown to reduce the risk of falls in older adults. 5 Recommendations from occupational therapists including improving lighting, reducing clutter, painting the edge of steps, installing grab bars and stair rails, and removing or changing throw rugs have been shown to reduce the number of falls and the risk of falls in older adults.21-23 Knowledge about where injurious falls are most likely to occur in the home and how they differ by both sex and age group may help older adults prioritize the numerous home modifications that might be needed and are costly to implement. For example, a higher percentage of adults aged 65 to 74 fell on the stairs than any other location in or around the home. Making sure stairs have rails and appropriate lighting may be especially important for this age group compared to modifications in other areas of the home.

It is important to note that home hazards are not the only modifiable risk factors associated with falls among older adults. Other modifiable risk factors include poor strength, gait, and balance, use of certain medications, postural hypotension, impaired vision, and improper footwear. 24 The greater the number of fall risk factors older adults have, the higher their risk of falling. 25 Fall prevention programs should include multiple components to address not only home hazards, but other modifiable risk factors. 26 For example, bedrooms were a common location for injurious falls, especially among adults aged 85 and older. Removing tripping hazards in the bedroom may prevent an older adult from falling; however, addressing postural hypotension or reducing medications that increase frequent nighttime urination are also important in reducing these falls. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI) initiative guides providers in recommending fall prevention activities based on their patient’s individual modifiable risk factors. STEADI includes recommendations for home safety checks conducted by a health care professional such as an occupational therapist and consultation with a pharmacist to review and make recommendations on how to optimize medication use for improved health and reduced fall risk (www.cdc.gov/steadi).

This study has several limitations. First, approximately 40% of fall-related ED visits could not be attributed to an indoor or outdoor location and approximately 50% of falls that occurred at home could not be linked to a specific location in or around the home. This was mostly due to short narratives only capturing 1 to 2 sentences describing the circumstances of the injury. Results of this study should be interpreted cautiously due to the large percentages of unknown locations. Second, it is possible that the way location variables were coded influenced some of the differences found in this study. It was easier to identify some specific locations around the home than others. For example, it was simple to determine a fall happened in a bedroom if bed was mentioned in the narrative; however, for living room we relied on clues such as couch or recliner, which could be found in other locations but were coded as living room. We did not divide locations of falls that did not occur at home into smaller categories due to the difficulty in determining the specific location of falls not-at-home (eg, the difference between falling on a sidewalk vs falling on the street). Furthermore, residential facilities were only captured if specifically mentioned in the narrative, it is possible that some fall injuries occurred among those living in residential facilities but were coded as community dwelling. Additionally, it is possible that the location of older adults’ fall injuries differs by variables not included in NEISS-AIP data, such as socioeconomic status and comorbidities. Future studies about location of older adult falls may benefit from additional information about demographics. Time spent at different locations could not be determined from the NEISS-AIP dataset. It is possible that a majority of older adults reported falling at home and in their bedroom, stairs, or bathroom because older adults spend more time in these locations. Finally, fall injuries seen in EDs are a subset of injuries and falls overall, information about the location of falls or injurious falls not seen in the ED cannot be determined from this study.

Conclusion

Among older adults who had a fall-related ED visit in 2015, indoor falls were more common than outdoor falls. When the location of the fall could be determined, older adults more commonly fell inside the home and more specifically in a bedroom, on stairs, or in a bathroom. These findings suggest that older adults should be aware of hazards in their homes. If conducted at the population level, home modifications could avert more than 120 000 falls and $442 million in health care expenditures each year. 27 In addition to home modifications, other modifiable fall risk factors such as gait impairment, postural hypotension, and vision impairment should be considered. Health care professionals can screen, assess, and intervene to reduce their older patient’s modifiable fall risk factors and offer solutions to help them remain healthy and independent longer.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_A for A Descriptive Analysis of Location of Older Adult Falls That Resulted in Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2015 by Briana L. Moreland, Ramakrishna Kakara, Yara K. Haddad, Iju Shakya and Gwen Bergen in American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tadesse Haileyesus, MS (mathematical statistician), with the National Center of Injury Prevention and Control for his guidance with coding and analysis of the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-All Injury Program data.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The findings and conclusions in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

ORCID iDs: Briana L. Moreland  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2144-1513

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2144-1513

Gwen Bergen  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0391-6738

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0391-6738

Contributor Information

Briana L. Moreland, Division of Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; Synergy America Inc. Duluth, Georgia.

Ramakrishna Kakara, Division of Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Yara K. Haddad, Division of Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia TJFACT Pharmacist Consultant.

Iju Shakya, Division of Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Gwen Bergen, Division of Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WISQARS™: injury data. Accessed May 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- 2.Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and fall injuries among adults aged ≥65 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:993-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns E, Kakara R. Deaths from falls among persons aged ≥65 years—United States, 2007-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:509-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER. Accessed May 2020. https://wonder.cdc.gov/

- 5.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD007146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boye ND, Mattace-Raso FU, Van der Velde N, et al. Circumstances leading to injurious falls in older men and women in the Netherlands. Injury. 2014;45:1224-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duckham RL, Procter-Gray E, Hannan MT, Leveille SG, Lipsitz LA, Li W. Sex differences in circumstances and consequences of outdoor and indoor falls in older adults in the MOBILIZE Boston cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelsey JL, Berry SD, Procter-Gray E, et al. Indoor and outdoor falls in older adults are different: the maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and Zest in the Elderly of Boston Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2135-2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelsey JL, Procter-Gray E, Berry SD, et al. Reevaluating the implications of recurrent falls in older adults: location changes the inference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:517-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiller JS, Kramarow EA, Dey AN. Fall injury episodes among noninstitutionalized older adults: United States, 2001-2003. Adv Data. 2007;(392):1-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timsina LR, Willetts JL, Brennan MJ, et al. Circumstances of fall-related injuries by age and gender among community-dwelling adults in the United States. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deprey SM, Biedrzycki L, Klenz K. Identifying characteristics and outcomes that are associated with fall-related fatalities: multi-year retrospective summary of fall deaths in older adults from 2005-2012. Inj Epidemiol. 2017;4:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James MK, Victor MC, Saghir SM, Gentile PA. Characterization of fall patients: does age matter? J Safety Res. 2018;64:83-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leavy B, Aberg AC, Melhus H, Mallmin H, Michaelsson K, Byberg L. When and where do hip fractures occur? A population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2387-2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens JA, Haas EN, Haileyesus T. Nonfatal bathroom injuries among persons aged ≥15 years—United States, 2008. J Safety Res. 2011;42:311-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill AM, Hoffmann T, Haines TP. Circumstances of falls and falls-related injuries in a cohort of older patients following hospital discharge. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:765-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroeder T, Ault K. The NEISS Sample: Design and Implementation. US Consumer Product Safety Commission; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Consumer Product Safety Commission. NEISS: The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System: A Tool for Researchers. US Consumer Product Safety Commission; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques. 3rd ed. John Wiley; 1977:327-358. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff GJ. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:55-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, La Grow SJ, et al. Randomised controlled trial of prevention of falls in people > or = aged 75 with severe visual impairment: the VIP trial. BMJ. 2005;331:817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikolaus T, Bach M. Preventing falls in community-dwelling frail older people using a home intervention team (HIT): results from the randomized Falls-HIT trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:300-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pighills AC, Torgerson DJ, Sheldon TA, Drummond AE, Bland JM. Environmental assessment and modification to prevent falls in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:26-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75:51-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1701-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons, American Geriatrics Society and British Geriatrics Society. Summary of the updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:148-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens JA, Lee RJ. The potential to reduce falls and avert costs by clinically managing fall risk. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:290-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Appendix_A for A Descriptive Analysis of Location of Older Adult Falls That Resulted in Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2015 by Briana L. Moreland, Ramakrishna Kakara, Yara K. Haddad, Iju Shakya and Gwen Bergen in American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine